Endless and beautiful Lake Michigan

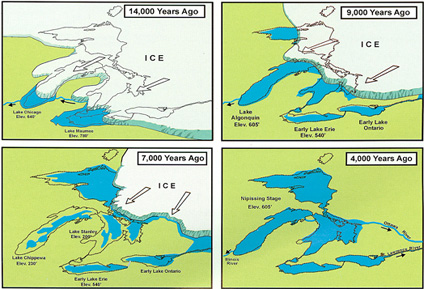

In 1998, a permit was accepted by the government of the Canadian province of Ontario, following a lightly-remarked-upon 30-day public comment session, to approve a ridiculous and pointless money-making scheme. This approval set in motion a multi-national effort to protect one of the great natural treasures of the world, one that could decide the future of water on an increasingly parched planet, and one that will shape the fate of a harmless Milwaukee suburb, whose destiny lies on its placement just east of the slight bend of a continent, a product of ancient and mute geological forces. It’s a story about our distant past, and one about our every-drawing future.

It was in 1998 that a businessman, John Febbraro, applied for a permit to have giant tankers scoop up water from the Great Lakes– specifically the giant of the group, the vast and violent Superior– and sail them through Sault St. Marie, down through Windsor, up through Erie and Ontario, into the vast river of the St. Lawrence Seaway, and then to Asia, where a thirsty market would gobble fresh water. (This is detailed excellently in Peter Annin’s Great Lakes Water Wars, a must-read for anyone interested.)

It was an amazing plan, and a ridiculous one, born of a good idea that made absolutely no sense. Febbraro planned to scoop up 427,000 gallons a day, which comes up to around 155,885,000 million gallons a year. That seems like a lot, until, as we see, that comes to about what an average-sized suburb of Milwaukee would need in a 6-month period. That…won’t solve any Asian water problems.

But still, it proved a catalyst. There was a Great Lakes Charter signed in 1985, by the eight US states and two Canadian provinces the have land bordering the states (which yes, includes Indiana). But it turned out that the Charter wasn’t very strong, which is why a plan to take water from the Lakes and ship it around the world could be approved.

The plan provoked outrage, and incredibly enough, action. Pressure- and honestly, the economic infeasibility and ridiculousness of the plan- destroyed Febbraro’s dream. But more than that, it spurred people, Democrats and Republicans, Labor and Conservative, into recognizing that the Great Lakes weren’t permanent, and could be destroyed. Just because the plan to have boats take water to Asia was absurd- and anyone who has watched giant ships sail by, dwarfed by the enormity of this water, could tell you it was absurd- didn’t mean the writing wasn’t on the wall.

After all, if a ship could take water, why couldn’t hundreds? Why couldn’t thousands? Why couldn’t pipelines be built to replenish barren reservoirs in Western deserts? While there was never a plan to make it economically feasible to do so (and many tried, both public and private), it didn’t mean it couldn’t be done. At some point, an economy of scale could take over, and it would make sense to trickle water out of the lakes.

But apres trickle, le deluge? That was, and is, the big fear, which is why in 2008 the Great Lakes Compact was signed. This was a guarantee that no one outside of the Great Lakes Basin could use water without the permission of every state and province in the region. The problem is– one of the problems is– that with the exception of Michigan, none of these states or provinces lie wholly within the Basin. Which means politics takes over.

And that leads us to Waukesha, a city the is a suburb of the Basin-included Milwaukee, but one that is just outside. Waukesha has spent years applying for a diversion, claiming that their source of water, underground wells, is dirty and mostly poisoned, and anyway won’t last them very long, and anyway, besides, they are so close. A swift walk can get you to the Basin; a decent bike ride to Lake Michigan; if you are driving, a day at the lake is like going down the street.

Most of the obstacles to their application have fallen. Last month, the Great Lakes Compact group voted 9-0 (with Minnesota abstaining) to approve the diversion, with serious conditions. Next week in Chicago, the final governor-level meeting will take place, to decide its ultimate fate.

So, this is Great Lakes water week here at Shooting Irrelevance. It’s a story of politics and the environment. It’s a story of the future of water, and how we’ll use it, and most importantly, who owns it. After all, if the Lakes are a public good, why should greedy Chicago (who has the mother of all diversions) luxuriate while citizens in Nevada parch? It’s a story about political geology, and how these ancient forces shape our present. It’s a story of competing activism, in which every side has moral ground. Mostly though, and fully, it’s a story of the Great Lakes, this gorgeous and perfect and tempestuous system. It’s a story about their strength, and their fragility.

When you stand on the southernmost edge of the system, as I often do, at that sweeping curve that defines Chicago, they seem infinite, overwhelming, almost impossible in their magnificence. You can drive for hours and hours, up the coast of Wisconsin, and around the UP, and still have barely covered half the shoreline. They are amazing, and they are not like the ocean, which are essentially inhuman in size. The Lakes, though enormous, are human. We’ve paddled across them for millennia, traded across them, sent great ships to ply them, but also to sink. To sink in their temper, in their violence, in their sudden reminder that they are not ours to do with what we like. It’s a warning, a reminder that there are enormous ships on the bottom of these lakes, the Edmund Fitzgerald and the Carl Bradley, that were swallowed whole. But it is also a fearful warning. There is no consciousness in lakes, but if there were, they would look at the tragedy of the Aral, and ask us to stop and think. They’d remind us that, in our tempers and ill-humors, in our short-sightedness, we can ruin a great gift.

That’s what we’ll be talking about this week; ultimately, the tragedy of competing and rational human interests in the face of unconcerned nature. Hope you’ll enjoy. Here’s a rough schedule.

- Tuesday: the political geology and geography of Waukesha and the Lakes

- Wednesday: an analysis of the Waukesha proposal and its opposition

- Thursday: Activism and the Great Lakes: A Model for Environmental Impact

- Friday: What it all means; or, the future of water.