Last week, when it was announced that the jury in the Derrick Chauvin case had reached a decision on whether or not to convict the former cop in the clear-as-day murder of George Floyd, there was an odd tension. Everyone knew he was guilty. Everyone adduced that the jury’s swiftness indicated one result. But all that surety almost added to the palpable cynicism: of course he’d get off.

That he didn’t, and was indeed indicted on all counts, was met with relief, but rarely with joy. Of course not — how could there be any joy? Floyd was still dead, and as so many of us rushed to social media to point out, this didn’t really mark a difference in the way policing in this country operated.

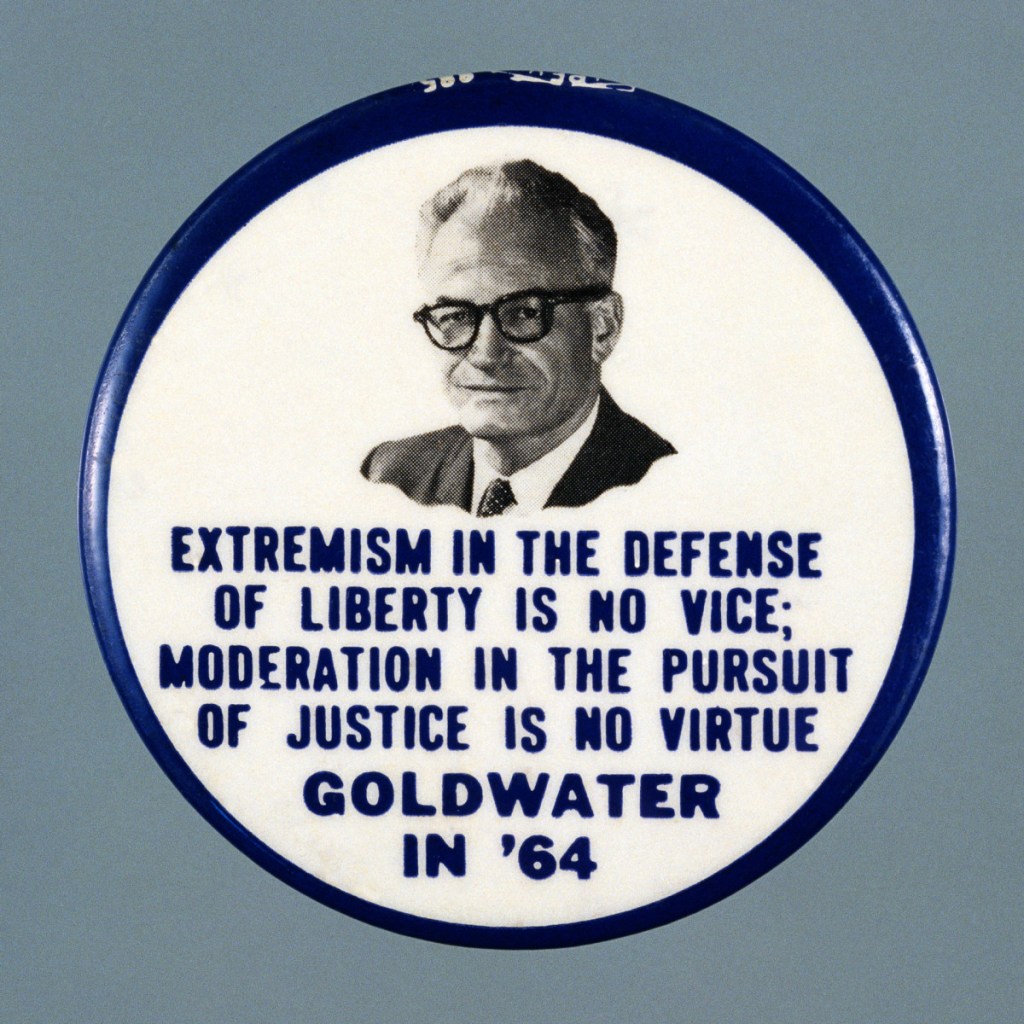

But what does that mean? What does “justice” mean in this context? If you were to ask me, I would have probably said something about how racial disparities were eliminated and the police no longer treated non-whites as an occupied people. “Justice”, I’d intone, “is not when George Floyd’s murderer goes to prison,” (dramatic pause, lip bite) “but when no one has the power to murder George Floyd under the flag of Law.”

You have to admit that “the flag of Law” would have been a nice touch, but then you’d ask: so, what does that mean?

And that’s where I’d falter. That’s where my edifice of justice starts to crumble. Because the truth is that I don’t know what that means. For me, those words are almost an act of magic. It’s a sentence that sounds good.

That’s because I, like so many liberals and leftists in this country, have not done the work to grapple with the fundamentals of the system. Because of that, the solutions seem both easy to say, and impossible to imagine.

For me, facing someone who has done the actual work is almost as impossible.

Mariame Kaba has done the work. Kaba, better known to most people in the online community through her blog Prison Culture and her twitter handle @prisonculture, has actually been working with the idea of what this kind of justice means.

I was reading her new collection of essays and interviews, We Do This ‘Til We Free Us, last week when the results of the trial were coming in. This exact timing was a coincidence, but that I was reading it — or the book existed at all — was not.

The murder of George Floyd, the national outcry, the protests, and the immensity of the police violence that followed, moved more people into a radical direction than I think anyone had ever thought possible.

Anecdotally — but anecdotes borne out by data and by our politics — people started to question what the police actually meant, and why they were needed. I know so many people who were liberal-but-still-hated-hippies who went full “fuck the police” over the summer. Older liberals started truly seeing the darkness. It was in this milieu that “abolish the police” started to be heard.

Police and prison abolition is work that Kaba has done for decades. It’s work that she has explored, thought about, perused, and worked. This, then, should have been her moment.

In a way, it was: there was certainly more exposure for her work than ever before. But in the mainstream liberal-left, the argument tended to break down into two sides.

- No, we don’t actually mean “abolish the police” but it is a useful slogan to think about shifting funds into more community services while keeping police for limited duties while still making sure they are very regulated.

- Yes, get rid of them, yesterday.

The first one is a throat-clearing misrepresentation of how truly radical the notion of abolitionism is. And the latter is in its own way even a greater misrepresentation of the movement’s true radicalism. The idea isn’t just to get rid of the police because they are a corrupt, racist, violent paramilitary. It is to change a corrupt, racist, violent, militaristic society so that the police are no longer needed.

Now, this is where the argument begins to losE people like me. Let’s call us “wise people” because we like to think of ourselves as so. “Well that’s all well and good to think about, but what does that even mean? Is it not a pipe dream?”

Pipe dreams, for me, are comfortable. If I can call something a pipe dream, then I can pretend it isn’t serious, or at least not achievable, and continue to march and donate to mutual aid and all that without having to actually do something. It’s all well and good to imagine a different society, but we live in this one, don’t we? What would we do if there were no cops? Be serious.

Kaba’s great power is that she is deadly serious, because she’s done the actual work of thinking through what this all means. She forces people like me to actually confront the actual work. She doesn’t try to persuade through comforting pieties. She is not writing for me. But her words force me to turn my own pieties against themselves.

There’s an early example in the book, an essay from October 2020 entitled “So, You’re Thinking About Becoming an Abolitionist”, where she differentiates between what is criminal.

Moreover, crime and harm are not synonymous. All that is criminalized isn’t harmful, and all harm isn’t necessarily criminalized. For example, wage theft by employers isn’t generally criminalized, but it is definitely harmful.

This seems like a very simple argument. Sure, we all agree wage theft is bad. But very few of us would say that employers who engage in wage theft deserve to be in prison. After all, they are just stealing not-yet-earned money from people’s lives, as opposed to someone who steals money (whatever money means) from someone’s wallet.

But why is that different? Why shouldn’t the wage thief go to prison?

Or, more accurately, why should the traditional thief? If we believe that one kind of theft is ok, and punishable maybe by fines or something, why should the other one rob someone of their life for years or decades of grinding cruelty and systemic violence?

That, to me, is where the whole thing starts to get really uncomfortable. Because it shows that how we think about criminality is, essentially, random. And when you start to think about that…well, what else do you have to confront?

What Kaba does is make everyone confront the reality while presenting what could be. What it is is an act of imagination. In the same essay, she says that our adversarial court system is set up to create these adversarial positions, this godly idea of guilt and freedom. It removes accountability by placing fate in the hands of the a third party — and we take that as a natural law. Kaba writes that the “abolitionist imagination takes us along a different path than if we try to simply replace the (Prison Industrial Complex) with similar structures.”

It’s this “imagination” that is key to the project of abolitionism of prisons and police. It’s not, for Kaba, a matter of saying “no more police”, but a matter of creating a society where such a thing isn’t needed. It’s asking “what would it be like if we didn’t organize our society around the mostly-race-based carceral violence it’s been organized around since forever?”

To me, there is a slight parallel with Milan Kundera saying that the only way to live under the absurd but deadly literal totalitarianism of Czechoslovakia was to live “as if”: as if you were free, as if imagination was allowed, as if irony was the currency of life. Kaba is insisting that another way is possible and organizing and acting as if we already know the goal. The parallels between Czech communism, the tanks of 68, and the POC experience in America aren’t far off. As Kaba says elsewhere, “Black and brown people know that the state and its gatekeepers exert control over all aspects of our lives. This is not knew.” (I, belatedly, agreed.)

This act of imagination works backwards. It conjures up a society of transformative justice, of equality and freedom, of intersectional approaches to everything in life — the spectacular and the mundane — and works backwards. It imagines a world filled with mutual aid, or community accountability, and of an operation outside the confines of what we assume is the natural order of law and order, and organizes backwards from there.

Now, I want to be careful here, for a few reasons, that are tied together. I don’t want to oversimplify the arguments her and other serious abolitionists have made. There is enough of that on both the right and the left, and it gives people an out.

When that world, that future, is described as “imagination”, it makes it seem unserious. It allows for “serious” people to say that it is a pipe dream, and if we are well-meaning to advocate, even advocate ferociously, for piecemeal reforms that keep the system intact. (A brief instructive chapter is titled “Police ‘Reforms’ You Should Always Oppose”; the bulk of them are what s proposed every time we cycle through these endless cycles.)

But “imagination” here is misleading. It doesn’t mean “make believe”. It means asking what kind of world we want, and then doing the work to get there. As Kaba says, in a line she got from a nun, “Hope is a discipline.” It’s not about wanting something. It’s about working for it.

This is where her philosophy is both urgent and unrelenting and also long-term. One thing that keeps coming up throughout the book is a captivating modesty (and not only that she was reluctant for decades to put her name on the work she was doing). But she talks of how she is just part of the work of building a new society. Not only does she acknowledge that there is no clear finish line, but that this is the work of generations, and will not come close to fruition in her lifetime.

That’s hard to acknowledge if you are an activist or if you care. Or, let me be more accurate: that’s hard to acknowledge if you are an activist because you want to feel better about things. I can’t speak for true activists; they are lit by fires that I can’t bellow. But for myself, someone who is involved, the idea that change happens outside of my lifetime is extremely difficult. And the reason why is even more uncomfortable to acknowledge.

I can’t fathom a different society. I can’t imagine the world that Kaba and the other activists are envisioning and fighting for. And not (just) because it is so much work, but because I am the beneficiary of these cruel systems. They were set up for someone like me. And so it is much easier for me to imagine short-term solutions, fight for those, and feel good. Because a world in which everything we have now is inversed is a world in which I, and not just the bad people in riot gear, have to change.

Abolitionism doesn’t mean a reorganization at City Hall; it means tearing down the racist and classist and sexist and fear-based and cruel systems that were built by fearful and cruel racists and classists. It means acknowledging not just that the wallpaper is off, or that the plumbing is wonky, but that the whole damn house was designed by cannibals and built out of bones and its weight is borne by the suffocating masses underneath trying not to hold it up but to stave off its crushing, choking weight. That we can’t fix the house, but we have to move out of it, to blow it up, and to plant something new in the garden.

And so it is easier to ask “ok, but what about rapists?” and handwave off her long-term ideas about changing a culture of sexual violence. It’s easy to ask “and what of murderers, hmm?” than to engage with the idea of a violent society. And, to be sure, I don’t quite think that these are addressed by the idea of community accountability, but I am also vested in not having that imagination.

Kaba and other abolitionists don’t give themselves that luxury, and she admits that not everything is ironclad. That makes it easy to scoff, but in a long passage talking about failure in an interview, she basically says “fuck that”.

The freaking tech folks and the people who are running the banks talk about failure all the time. They normalize it. It’s only on the other side of folks who are interested in social transformation and change where failure is not supposed to be spoken about or a sign that you’re horrible or that your ideas don’t have merit. I just want us to be building a million different experiments….We’ll figure it out by working to get there. You don’t have to know all the answers in order to be able to press for a vision.

That seems correct. It isn’t evasion. It’s having an idea and making it happen. It is fiercely demanding immediate change and justice while working on a long-term vision to make a world where even more change is possible. That means organizing, teaching, building networks, creating workshops, teaching teachers, listening, learning, making mistakes, and moving forward. It’s endless, tiring work.

As Kaba says, not everyone is an abolitionist. Some of us just can’t do it, or genuinely want a graded step. But it is serious moral duty of anyone interested in transforming justice, anyone who has been made more radical, either slowly or all at once, to respect those who have done the work, to engage with their arguments with the same seriousness with which they are making them, and to support their vision of a world where we don’t have to have these arguments.