Of all the lies America officially tells itself, one of the strangest is that “We have never occupied conquered territory.” The story goes that since the US didn’t occupy Germany after either of the wars, nor did we take any Japanese territory, there is a nobleness to our cause.

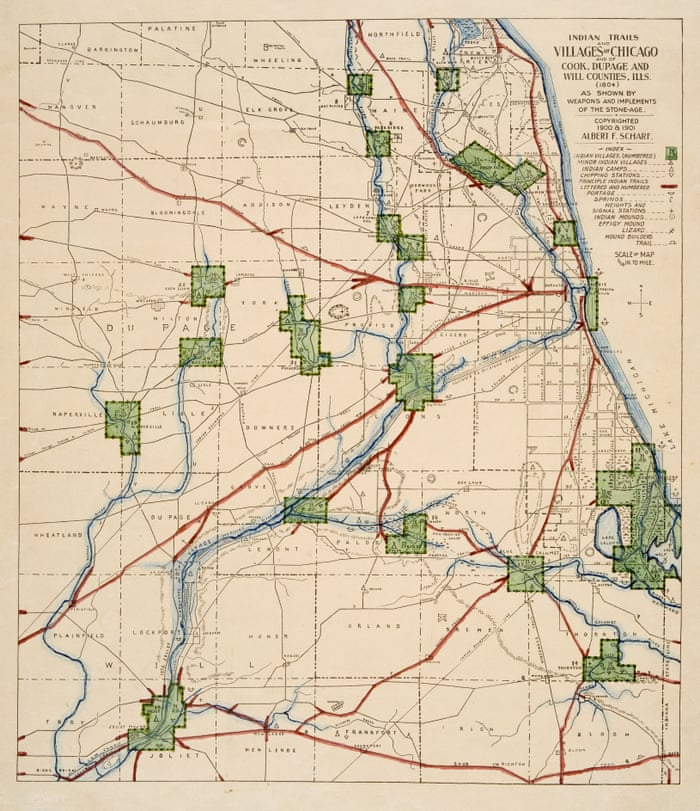

Needless to say, that’s absolute bunkum. There is not a single region of this country that wasn’t taken from Natives. Yes, the Louisiana Purchase was from France, but of course, it wasn’t filled with Frenchmen who immediately left: it was filled with Natives who were promptly extirpated.

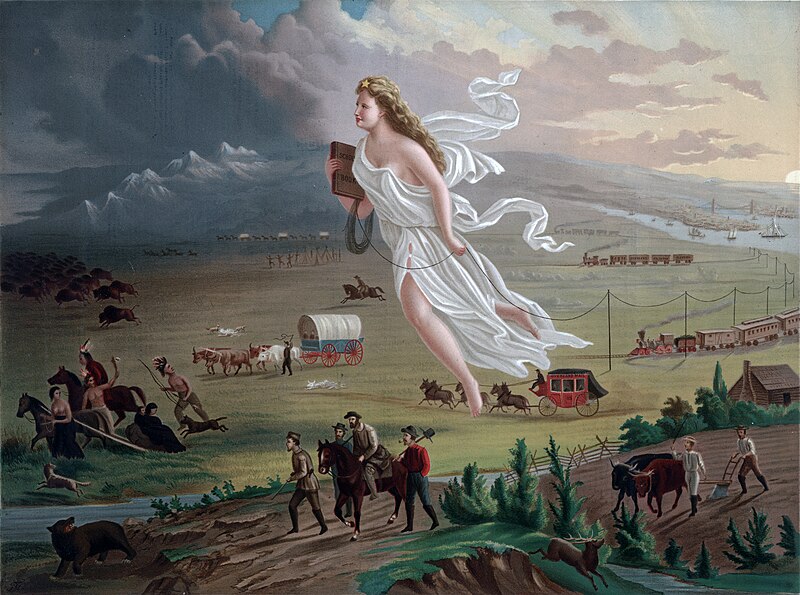

Of course, if any action gives immediate lie to that notion, it is the occupation and annexation of enormous amounts of Mexican territory following the brutal and phony war of 1846-1848. The occupied and stolen territory gave America its western bulk; it made destiny manifest.

One thing that America does very well is rapidly internalizing our myths. It doesn’t matter that the war was pushed by southern slave interests hoping to create an empire of chattel. It doesn’t matter that the secession of Texas was a reaction to Mexico outlawing slavery. While a mere 20 years later slavery was defeated, the idea that this territory was anything but given to the US by God was not even entertained.

The idea of these stories, and how they have shaped the American character, is the focus of Greg Grandin’s sweeping The End of the Myth, an electrifying read which takes you from the Cumberland Gap to Gettysburg to Martin Luther King’s radicalism to the perfidy of NAFTA, all with a unifying theme.

That theme is that of the frontier, specifically, the frontier as famously articulated by Frederick Jackson Turner. The nut of the thesis, developed by the then little-known Wisconsin academic in 1893, is that “(t)he existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward explain American development.”

It’s complicated, but basically that the waves of expansion (which are neither steady nor consistent) are what drives the American spirit. People come out, fight and die, scratch out an existence, fall back, push forward, etc. The land is tamed, capital moves in, people get itchy, and go to the next frontier. Violence, horror, success, railroads, and so on.

Now, you can (and should!) quibble with the idea that the land was “free”; the need for violence in the form of the US Army disproves that myth instantly. But the land was, I suppose, gettable. It could be got if you knew the right people (i.e. the US Army).

Grandin doesn’t so much deflate this myth as expose it for what it has always been: a pernicious way to both foment and excuse violence and expropriation while running a constant scam against the idea of freedom itself.

To back this, Grandin paraphrases Martin Luther King, who argued that the ideal “fed into multiple reinforcing pathologies: into racism, a violent masculinity, and a moralism that celebrates the rich and punishes the poor.”

This is all true, and it plays itself off as a sort of devil’s bargain. As Grandin explains:

There is a lot to unpack in the argument that over the long course of US history, endless expansion, either over land or through markets and militarism, deflects domestic extremism. How, for example, might historical traumas and resentments, myths and symbols, be passed down the centuries from one generation to another? Did the United States objectively nned to expand in order to secure foreign resources and open markets for domestic production? Or did the country’s leaders just believe they had to expand. Whatever the answers to those questions, the United States, since its dounding, pushed outward and justified that push in moral terms, as beneficial equally for the people within and beyond the frontier.

The frontier was a constant regeneration, taking the traumas of conflict and using them to start another battle, another front. Perhaps the most interesting part of the book talks is the section on the Spanish-American war, a conflict so ginned up it made the Mexican-American war look honest.

In our accepted history, the Spanish American war is a completely different era than the Civil War. That’s just how history is often taught; separate eras split by thick black lines and different quizzes. But of course, it was barely 30 years after that conflict ended. Most of its veterans were still alive. This was also barely 20 years after Reconstruction came to an ignoble and murdered end, unleashing a wave of democratic suppression and racist terror that persisted for 100 years.

And, as Grandin explains, basically no one was more excited about the Spanish-American war, and the colonial occupations that followed, than ex-Confederates. This, for them, was a way to be welcomed fully back into the American population, to prove themselves as fighters, and to kill non-whites. The Confederate flag flew over Cuba, and the Rebel Yell was heard in the Philippines.

Why does this matter? Because it was another expansion of the frontier. It was a way to regenerate the American myth after the Civil War and (maybe just as importantly) after Reconstruction. Grandin skillfully weaves the betrayal of Reconstruction with the dark decades of Jim Crow, Martin Luther King, Vietnam, and more.

This makes sense, when you start to look at American history as a continuous thing, and not something that actually happens in waves. The war for Mexican territory was fought to expand slavery. It was fought to create an American empire across the continent. The stories that we told about it- pablum about freedom, the brave men of the Alamo, standing up to an oppressive Mexican government who hated freedom so much that they outlawed slavery- was part of the same story we told ourselves of the Lost Cause, the noble South, the valiant Lee: stories that still exist.

And that, ultimately, is the lesson here. These stories are still being told, but there is nowhere left to go. The frontier has reverberated. Grandin takes us back again and again to the border, as it becomes militarized, filled with swaggering racists, both in real uniforms and in the jackal armament of vigilante militias. He brings us to a border suddenly filled with factories and economic refugees. He brings us to a border where people fleeing American-led violence in Central America end up. He brings us to a border whose fences, a cynical bargain made to pass NAFTA, trap people on both sides and make crossing a mortal threat.

In short, he brings us to today.

Trump and the End of the Myth

If you were to say one good thing about Donald Trump- and Christ, you really shouldn’t- it is that by being so openly vulgar, with such id-driven racism, and supplemented by such cowardly sycophants, he has forced us to recognize the cruelty that has always driven much of American policy.

Whether it is in Guantanamo Bay or when trying to gut health care or when locking up children in cages, performative, sincere cruelty (or, making a huge show of how sincerely cruel you are) is the Republican default position. Indifference to that cruelty has driven much of the so-called opposition, as well.

Reading Grandin, this makes sense. The frontier has always allowed us to push that cruelty outward, to find newer enemies, and to believe in regeneration. But now there is nowhere to go. Our wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (and everywhere else) are dim echoes of empire, grinding distant slogs only remembered with the faintest pantomimes of covered-heart “gratitude.” Global capitalism is seen as a dumb joke played on all of us, with the benefit that it is also destroying the present. The frontier, long-rumored to be dead, is officially gone.

That’s why Trump’s wall is the true end of the myth, as Grandin’s subtitle implies. We’ve been heading that way. It could easily be argued that violence against Mexico is just as much a part of the American character as slavery and genocide. It has been a centuries-long preoccupation (and real occupation). And now it has found its post-Polk apotheosis, at a time when everything seems to be crumbing.

Trump’s wall is the closing of the frontier, a sealing off of even a hypocritical American dream. And we have, just today, entered a new phase.

The firing/resignation/who cares of Kirstjen Neilsen is concentrating power in the hands of Trump and the wiry evil of anti-immigrant fanatic Stephen Miller. Today was a purge, as Mark Joseph Stern explained.

After firing Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen Nielsen on Sunday, President Donald Trump purged the agency’s senior management on Monday. According to CBS News, Trump secured the resignation of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Director Lee Cissna, DHS Undersecretary for Management Claire Grady, and DHS General Counsel John Mitnick. He also fired U.S. Secret Service Director Randolph “Tex” Alles. Trump adviser Stephen Miller, an immigration hard-liner, reportedly masterminded the DHS purge as part of an effort to crack down on immigration at the southern border.

So what does that mean? Well:

Trump didn’t want Grady; he wanted Kevin McAleenan, commissioner of Customs and Border Protection. It’s easy to see why. Under McAleenan’s leadership, CBP repeatedly broke the law to implement Trump’s first travel ban, earning a rebuke from DHS’ Office of Inspector General. McAleenan is a strong proponent of a border wall as well as new laws to curb asylum-seekers’ entry into the country. He infamously failed to inform Congress that a 7-year-old girl died in CBP custody when he testified before the Senate just three days after her death.

In other words, the real hardliners are taking over. I don’t know if Nielsen was a true believer or just a spineless sycophant, and she deserves a lifetime of scorn and opprobrium either way, but apparently there were lines even she wouldn’t cross. With this purge, the Trump people are looking for people who don’t believe in lines.

We’re living in an era of a hyperactive Border Patrol who are setting up Constitution-free zones in 75% of America’s populated areas. It’s an era where ICE is given full reign to destroy people. These are the spears of the new America, and they are being molded in Trump’s lawless image.

There might be pushback (apparently, some CBP officials didn’t like Trump telling officers they didn’t have to follow the law). Trump wants us to believe that “the country is full”, which is of course laughable, except he doesn’t mean it literally. He means that we have enough brown people, and we don’t want anymore.

And that’s the heart of the wall, and the heart of the frontier, and the heart of the American myth. That this is a land destined for white people, who can do no wrong. It’s why we believe that we don’t occupy territory when the whole country is occupied. It’s why we believe that land taken from Mexico has always been American, and why were are insanely resentful that anyone could question that. It’s why we take natural migration patterns as an affront to our sacred ideals.

The wall isn’t the antithesis of the frontier, it is its howling echo. It is its fulfillment. It is the promise of white nationalism with nowhere else to go, caged and furious. It is standing athwart history and pretending it didn’t happen. It is the stupidity of Trump and the cupidity of his enablers made concrete. It is the railroad and it is Pickett’s Charge; it is Custer and Andrew Jackson; it is James Earl Ray, and it is everyone who built their life around cheap consumer goods made by broken hands in child-filled maquiladoras.

The wall is the American Dream. It’s a reality from which we need to awake.